Beyond the Classroom: Two Teachers in the Field Explore Alaska’s Fishery Frontier

In September 2024, Teacher at Sea Alumni Jeff Miller (TAS 2015, Oregon II) and Kate Schafer (TAS 2017, Oregon II) spent time at NOAA’s Little Port Walter Research (LPW) Station in Southeastern Alaska, piloting a “Teacher in the Field” experience. The field station, located on Baranof Island, south of Sitka, is the oldest year-round biological station in Alaska. Researchers stationed there are conducting studies on a wide range of topics including Chinook salmon enhancement, shellfish mariculture, and developing efficient data collection methods for walleye pollock and Pacific cod. Kate and Jeff worked during the Chinook spawning season, one of the busiest times of the year. Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) are sometimes called “king salmon” due to their substantial size.

After traveling several hours to Juneau, Alaska from their respective homes in Arizona and California — Jeff and Kate eagerly awaited a clear weather window to travel to Little Port Walter. The field station is only accessible by float plane or boat, adding a level of difficulty to travel. After a one-day weather delay, Jeff and Kate were able to depart Juneau for a spectacular flight to Little Port Walter before settling into their quarters at the field station.

Research at the NOAA Little Port Walter Research Station

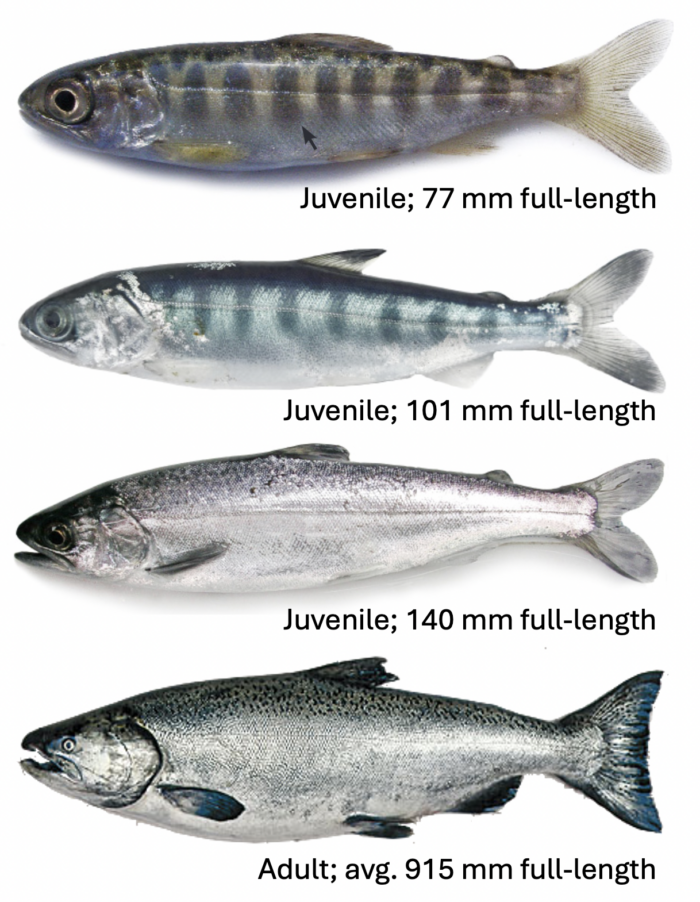

The primary long-term research project conducted at the Little Port Walter Research Station focuses on Chinook salmon and has documented salmon survival, run timing, growth, age composition, genetics, and environmental conditions since 1976. Chinook are the largest Pacific salmon species, growing (on average) to be two to three feet long and approximately 15-25 pounds. They can spend anywhere from one to six years at sea before they reach maturity and return to their natal river to spawn. The Little Port Walter Chinook salmon research program contributes key data for estimating harvest rates by commercial and recreational fisheries in Southeast Alaska and is important for Chinook salmon management under the Pacific Salmon Treaty. These long-term data sets also support efforts to characterize the impacts of environmental change on salmon population productivity and ecology.

The research station also plays an important role in the development of a sub-yearling broodstock of Chinook salmon. Currently, nearly all hatchery-produced Chinook salmon in Southeast Alaska are released as yearlings. Yearlings are incubated and reared in the hatchery for approximately 21 months prior to being released. However, this extended rearing is expensive and requires substantial space and water. As a result, there is considerable interest from industry and stakeholders to develop a broodstock of sub-yearling Chinook salmon, which only require ~9-12 months of rearing prior to their release. The development of such a stock would be much more cost effective and would increase the capacity of the hatchery facilities, as the space and water saved could be dedicated to the production of other fish. Little Port Walter researchers aim to develop a sub-yearling stock of Chinook for broader fisheries enhancement using fish from the Keta River, a unique system that contains a naturally-occurring sub-yearling component, which are released after just one year. If this project is successful, the sub-yearling broodstock would greatly reduce operating costs of Chinook salmon enhancement activities in Alaska.

Research at the station relies on identifying Chinook from Little Port Walter that are caught in commercial and recreational fisheries and accurately estimating the number of fish that survive to adulthood. To identify Little Port Walter salmon, young fish are tagged with a tiny, one-millimeter long metal tag called a coded-wire tag, which is inserted into the cartilaginous area of the fish’s nose. The coded-wire tags have six-digit numbers etched into them, and each hatchery has different numbers on their tags. Therefore, the numbers on the tags unambiguously link each fish to their hatchery of origin.

In a typical year, about 200,000 fish will be marked with a coded-wire tag and released from Little Port Walter into the ocean.

At Little Port Walter, returning adult salmon are captured using a fish aggregation device (FAD), gill netting, and a weir. The FAD is a series of nets that facilitates the capture of adult Chinook returning to Little Port Walter. Captured adults are then transferred to saltwater holding pens until they are ready for spawning.

In 2024, 1574 adult Chinook salmon were caught and processed for length, weight, sex, genetic samples, and fin clip status at Little Port Walter. Coded-wire tags were retrieved from 1153 of those fish and used to identify fish age, stock, and inclusion in the Regional Mark Information System (RMIS), which facilitates the exchange of coded-wire tag data among release agencies, sampling and recovery agencies, and other data users. The large number of untagged adults collected was a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, which precluded the tagging of juvenile fish from this cohort prior to release.

Spawning days are busy and require a collaborative and focused effort from all participants. The process is highly choreographed to facilitate quick and efficient collection of male and female gametes and data about each fish.

The spawning process is overseen by NOAA scientists Dr. Heather Fulton-Bennett and Dr. Charlie Waters together with Taylor Scott, the research manager at the Northern Southeast Regional Aquaculture Association (NSRAA), which collaborates with NOAA on the Chinook salmon project.

The broodstock for Little Port Walter come from the Keta River and are being reared experimentally in a joint effort between NOAA’s Auke Bay Laboratory and NSRAA. The Keta River stock tends to stay closer to the coast than some other Chinook salmon stocks and are thus available for harvest in the winter commercial salmon troll fisheries. Additionally, the Keta River stock tends to be a larger bodied fish, so fishers receive greater economic value when they harvest those robust fish.

The spawning process starts with the netting and euthanization of ripe fish (males and females ready to produce sperm and eggs). Holding nets are gathered up with an aluminum pole trapping the fish in an ever smaller pen. Once the fish are concentrated, they are netted and euthanized.

Fish are then transferred to the spawning deck where they are scanned to determine if they are marked with a coded-wire tag.

The fish are weighed and measured to document their size. A fin clip, which is used for genetic studies, is also collected.

The next step in the process is to extract the coded-wire tag from the fish. This step uses a specially designed tool to remove a tissue core from the fish’s snout, that is then waved near a tag detector (essentially a fancy metal detector) to determine whether the coded-wire tag is present in the core. Once the tag is detected in a tissue core, the core is passed on to another member of the team who dissects the coded-wire tag from the core, revealing essential information about the fish. Given the extremely small size of the tag, this takes patience and a keen eye for detail.

Meanwhile, the fish are transferred to Taylor Scott, who is the designated spawner and she retrieves the milt (sperm) from the males and the eggs from the females. The samples are stored in a refrigerator until they are transported up the coast to the NSRAA Hidden Falls hatchery facility. There the eggs and sperm will be mixed to create the next generation of Little Port Walter Chinook salmon. The juvenile fish generated from these spawnings will return to Little Port Walter the following spring to continue growing while they acclimate to an ocean environment.

Each day the young salmon are fed and “morts” (dead fish) are removed from the holding pens using a “mort sucker” designed by NSRAA and built at Little Port Walter.

In the fall, after the frenzied spawning work is done and the summer crew has departed, the nets on the pens holding the young salmon are dropped. The following morning, all the young fish are gone. Researchers are experimenting with a fall release time to evaluate their marine survival and compare to survival of Chinook smolts that are usually released in May.

All of this is hard work, but Kate and Jeff were able to take some time to enjoy the wonders of this remote Alaska location. They saw bears, hiked to waterfalls, visited a local museum, foraged a wide selection of wild mushrooms, and (of course) fished. They were also able to catch a great view of the aurora borealis before returning home to plan how to incorporate this experience into their teaching.

(Photo credits: unless otherwise noted, NOAA Teacher at Sea)