Classroom to Coastline: Bringing Together Educators

The third cohort of Project ROVe took place in July, 2024. In partnership with Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary, it was the first hybrid cohort, where local educators joined TAS alumni as participants. Local educators who were invited are interested in bringing Project ROVe to their local communities.

By La`akea Laano, TASAA Digital Communications & Events Coordinator

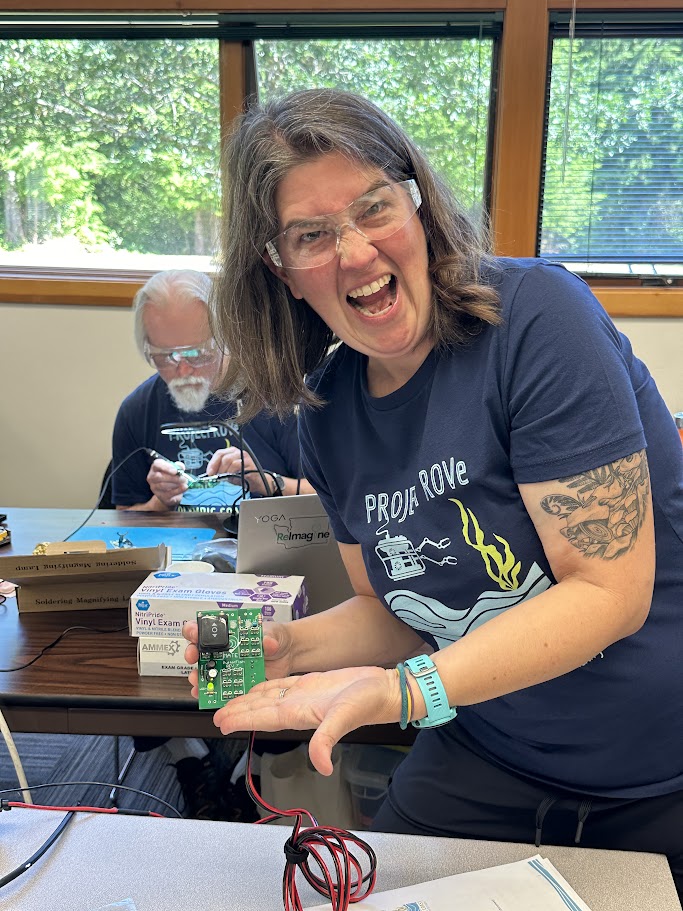

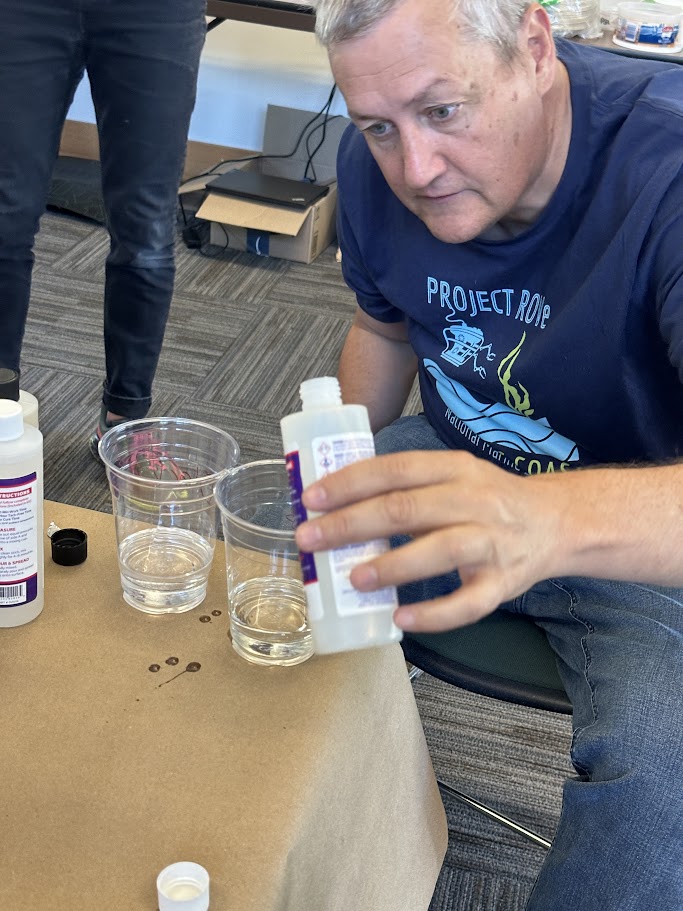

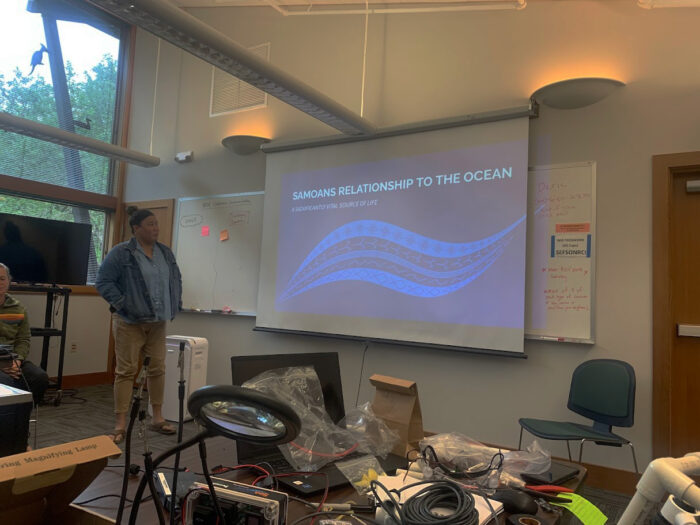

Teacher at Sea Alumni Association (TASAA), we often blog and post on social media about Project ROVe and its involvement in the MATE (Marine Advanced Technology Education) ROV competitions. If you haven’t participated in Project ROVe, or even feel intimidated by remotely operated vehicles (ROVs), it might feel like an aspect of TASAA that doesn’t include you. Even as TASAA staff, I’ve often felt a little on the outside of all this activity. But the recent Project ROVe workshop in Forks, WA opened my eyes to the ways in which this educational effort is a vehicle (pun intended) that benefits not only communities, but the teachers involved, and to how it increases inclusivity. This third Project ROVe cohort is the first to include TAS alumni, local educators from the Olympic Coast, and educational leads at partner sanctuaries. The “aha” moments came not only during the workshop itself, but also during excursions that connected our work to our host area, the Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary.

One evening, after the workshop had ended for the day, the group made an impromptu drive to the beach. On the way, we stopped at the restaurant at 3 Rivers Resort in La Push, for burgers and shakes. We ate our burgers in the presence of (cardboard) vampires, for which Forks is famous.

Then, it was a short hike through a dense, mossy, temperate rainforest where, at the end, the dense green curtains suddenly opened up to an ethereal foggy beach with sea stacks in the distance. It was moody, atmospheric, and awe-inspiring.

We walked along the beach, dipping our feet into the icy Pacific waters and crossing a small stream that fed into the ocean. It was an unfamiliar area for many of us, but we each connected to it in our own way. Staff participant Daniel Moffatt, from Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary’s cold waters of Lake Huron, ran to the frigid waters of the Pacific and proceeded to body surf through the waves. Our colleague Bel Halatuituia, from National Marine Sanctuary of American Samoa, looked across the horizon and felt a connection with her homeland. Coincidentally, workshop participant Bri Ashford’s daughter, an ROV aficionado, is a NOAA Hollings Scholar in American Samoa working directly with Bel and local students to build ROVs. The connections run deep.

On the hike back, Bri talked about how difficult the pandemic was, not only for students, but also for teachers. She described how rejuvenating this workshop was for her, giving her that lift and “breath of fresh air” that she needed. It was important for all of us to step out of, not only our individual classrooms and workplaces, but our shared classroom in Forks, to make the connection between the work that we do and why we do it. I also felt newly inspired by this notion: because teaching is such hard work, and often done without the physical presence of adult peers, it’s important that we, in education, support professional development that addresses not only content, but also teachers’ wellbeing, and sense of community and overarching purpose. For TASAA out-of-state travel buddies Lindsay Smith (TAS, 2011), Ashley Cosme (TAS, 2018), and Jennifer Bruce Petro (TAS, 2013), it was an opportunity to connect with other TAS over a shared experience, chat about ways they’ve implemented their TAS experience into the classroom and shake up their routines by exploring a new place.

Perhaps biased by my own set of skills, or lack thereof, I had a perception of ROV education as Something That Other People Do. People like robotics club members and kids who are already into that kind of stuff. But several teachers (from throughout the Olympic Peninsula, as well as American Samoa) talked about its impact on rural communities that don’t often have access to the kinds of opportunities available to urban-dwelling students.

Alice Ryan, a local Olympic Coast teacher talked about how it’s important for students to have meaningful, valuable connections to career opportunities within their own communities. The ROV program at her school is a great source of recognition for students’ academic endeavors, as evidenced by the many trophies displayed at the school. Her students have gained leadership skills, and become confident in public speaking. Bel described how, in American Samoa, the primary career choices are the military and football. For her students, ROVs provide a much-needed alternative option that is geared towards careers in STEM fields.

For Rosalind Echols’ (TAS, 2013) students at a maritime high school near Seattle, skills in robotics and engineering can lead to trade and vocational learning in lieu of a college degree. Rosalind also emphasized how, in addition to skill acquisition, ROV building creates a pathway to direct access to the marine environment that many students otherwise would not have. Bri echoed this, by describing the lightbulb moment for students when they are able to see underwater, via their ROVs, the community shoreline area that they’ve previously only seen from a distance.

Optional tidepool day at Kalaloch’s Beach 4

None of these moments or learning opportunities would have been possible without our continuously upbeat and enthusiastic partner and colleague at the Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary (OCNMS), Christine VanDeen. Her knowledge of the area gave us an insider’s experience of OCNMS that most of us will always remember.

For the TASAA team, bringing alumni together with local teachers in a National Marine Sanctuary reinforces our conviction that giving teachers ways in which to interact with the sanctuaries can exponentially increase engagement with these places, through the students they teach. Of equal importance is the opportunity to connect and inspire our teachers, who work hard to engage their students on a daily basis and who benefit from continuing education opportunities that allow them to collaborate with like-minded peers.

I began this story, both literally and figuratively, as an outsider. But learning the stories that everyone had to tell was a beautiful revelation. I now see Project ROVe as less about robotics and more about the human faces, about the collective action of lifting up our kids. About the from-the-ground-up efforts of people like Alice and Andrea to get this movement going, like little seedlings sprouting up from American Samoa to Massachusetts. This was not only my first in-person Project ROVe event, it was also my first in-person TASAA event. Yet it instantly felt like being with a group of people who are all on the same page, for whom positivity and contributing to their communities are an integral part of who they are.

Photo credits: Lindsay Smith, Ryan Hawk, Project ROVe