Finding Free Gifts in Nature Through Journaling

By Denise Harrington, TASAA NOAA Fellow

Spending time in the great outdoors was a cornerstone of my childhood. Many family vacations were enjoyed in the woods and I went on 50- and 70-mile hikes with the Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts. I was a fast hiker, gaining the nickname Billy Goat. This was not a terrible thing, but in retrospect, I missed a lot when I was speeding my way to the summit.

Fortunately, when I had children, they taught me the benefits of slowing down. When I could no longer carry my son Martin on my back, I watched him explore independently. He and his sister introduced me to the close-up world I had been sprinting past all these years. As we sat counting fish in a creek or looking at pebbles, I still felt the obligation to “do something” beyond just observing. So, I bought a small watercolor travel kit, a block of watercolor postcards, and a book for inspiration called One Small Square Backyard, by Don Silver.

I took my watercolor kit everywhere we went to document the incredible world around us. Watercolors became my door to the world of curiosity and discovery, a world that sometimes gets beat out of us in the gauntlet of standardized tests, afterschool programs, and loads of laundry. On these priceless days, we would head to the woods, beaches, or mountain tops and we would stop when something caught our attention. While my children observed, I painted and engineered one small square of the world. One day, on a lengthy stop, where time seemed to stand still, I painted these views of Neah-Kah-Nie Mountain looking north from Nehalem Bay. Another day, I painted the view of Nehalem Bay looking south from Neah-Kah-Nie Mountain.

From the peak of Neah-Kah-Nie Mountain, Oregon, looking south, I painted Nehalem Bay using my small watercolor travel kit.

I painted the same region as above, but this time from Nehalem Bay, looking north toward Neah-kah-nie Mountain.

Sometimes my children and I collaborated, sharing our focus with each other. Other times, we conducted solo observations of caterpillars, lichen on a stick, or dew on a leaf. With practice, I developed the mindfulness skill that my children seemed to have mastered from the start. Time spent outside, slowing down, observing, documenting, and gaining a deeper understanding of nature through art is so valuable to me that over the years it has grown beyond a family activity into a classroom mainstay.

Art in My Classroom

As the 2021-22 school year ended and I packed up my classroom to begin the Teacher at Sea Alumni Association NOAA Fellowship, I sorted through 15 years of student work that had accumulated. Combing through the materials allowed me to reflect on some of my favorite art and science activities, which also serve as the inspiration for the direction I plan to take during this fellowship year.

One of my favorite activities (also enjoyed immensely by my second graders) was nature journaling. Not only does this activity live at the intersection of art and science, but it was also a welcome opportunity to give students more time in nature. Beyond art and science, nature journals provide a way to integrate nearly every area of the curriculum seamlessly and in an engaging way. Additionally, each season brings natural phenomena—like seed dispersal, germination, and plant growth—to be observed. With their very first journal entry students become artists and scientists by observing, responding to, and recording the natural world around them.

Warming Up to the Great Outdoors

There are a few low-prep ways to get started with nature journaling and the nature journals themselves can be pieces of paper folded together if your budget does not allow for notebooks.

Listen

To get students focused, start with a 30-second timed listening activity.

- Students sit down and record everything they hear for 30-seconds with pictures and/or words; no talking allowed.

- After the 30-seconds is up, congratulate them on their first investigation.

- Now have them share their journal entry with a partner.

- Did they notice “new” sounds? What were they?

- Did they see “new” things? What were they?

- Did they hear and see the same things or different things?

- What do they wonder?

Look

A playful way to loosen up, gain focus, and increase artistic confidence in students is the observant contour drawing. In this type of drawing, students draw what they see without looking at the paper or lifting their pencils. The observant contour technique allows the artist to be completely mindful of the subject without any focus on the drawing itself.

In a modified observant contour drawing, they can occasionally glance at the page, but still do not lift their pencil.

From Dolomite Point, Haida Gwaii, I looked over the horizon and allowed my hand to record what I saw. After finishing the modified contour drawing, I added details with watercolor.

Characteristics of Good Journaling

Once students start to feel comfortable with the process of journaling and the need for focusing all their senses, it is useful to introduce some structure. To give students context for the importance of recording observations, I would share my experiences blogging from the NOAA Ship Oregon II and from my work as a wildlife surveyor where I began each survey entry with the date, location, and weather. Both the shark and owl surveys I worked on were designed to monitor populations of a particular species.

All things in an ecosystem are interconnected and being able to capture data consistently across time about an organism, as well as the conditions in which it lives, allows scientists to understand a species in relation to its surroundings. Over time, these data can be analyzed to understand why a population might be changing or to answer questions which may arise later.

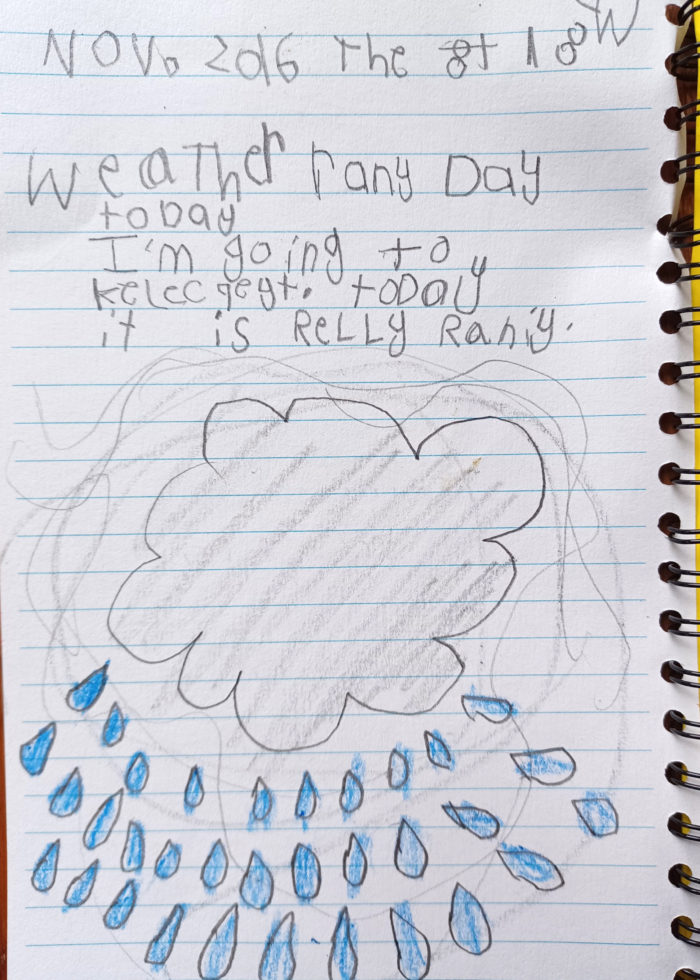

With the simple journaling routine of starting entries with the date, place, and weather, students join the legion of scientists who observe and record information to help us better understand our world.

Taking it to the Next Level

Shifting Perspective

Using a jeweler’s loupe, a magnifying glass, or a microscope can give students the opportunity for seeing and drawing things close-up.

- Have students examine an object and “zoom-in” and draw what they see.

- If using loupes or magnifying lenses, teach them how to identify when an image shifts from blurry to clear.

- Have them sketch the object.

- Have them write a response to the prompt “what does this remind me of?” For example, as I shift perspective, the underside of a leaf may remind me of a watershed.

As students zoom in and out with sketches, they gain experience with scale and perspective, and may begin to see similarities in shapes and other things found throughout nature.

Exploring Phenomena: Weather

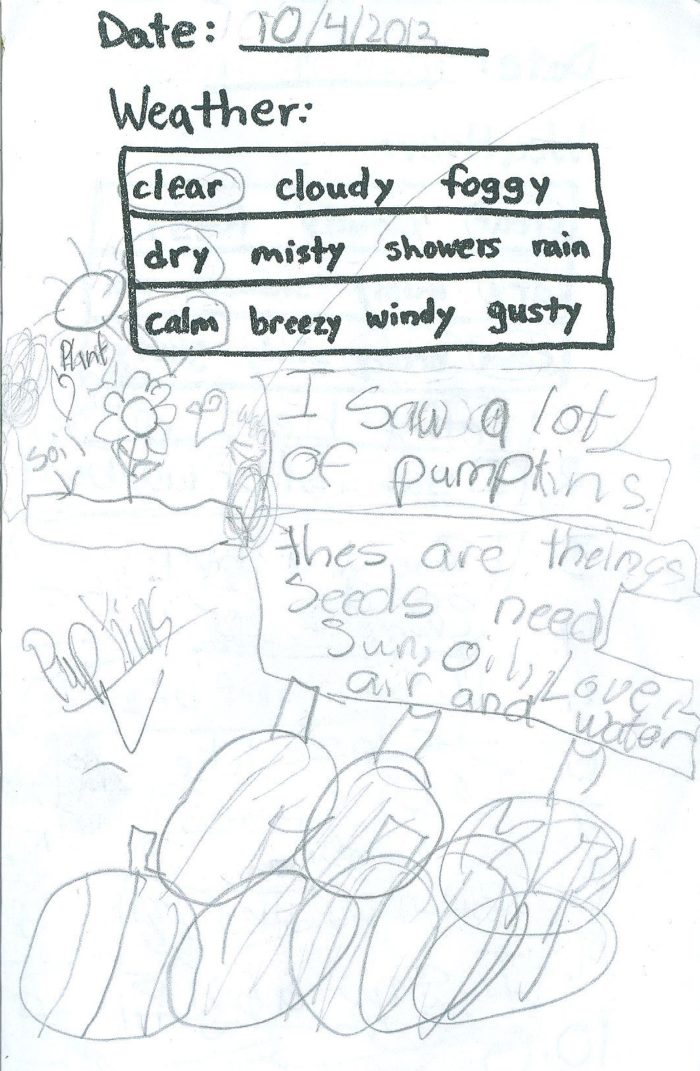

The three elements of weather I routinely recorded in my own field survey work were cloud cover, precipitation, and wind. So, I limited my instruction to these elements. I provided a simplified word bank for scaffolding as needed.

- Have students look at the sky. Is it clear, cloudy, or foggy?

- Have students feel the grass. Is it dry, misty, showers, or rain?

- Have students listen to the leaves in the trees. Is it calm, breezy, windy, or gusty?

Journal entries are a place for observation, reflection, and integration of core concepts. In a lesson at the pumpkin patch, students learned that plants depend on water and light to grow by making bracelets with a bead to represent sun, soil, air, water, and love. Having already recorded the weather, students then connected weather and climate with the plant growth activity in the pumpkin patch.

Each time we journaled, weather played a critical role in our experience. On this day in the pumpkin patch (picture to the right) we discussed the unusually clear, dry, and calm weather. Weather observations can lead to discussions about:

- How does the weather and climate impact the pumpkin’s growth?

- How do humans deal with these conditions to make sure they have a healthy pumpkin patch?

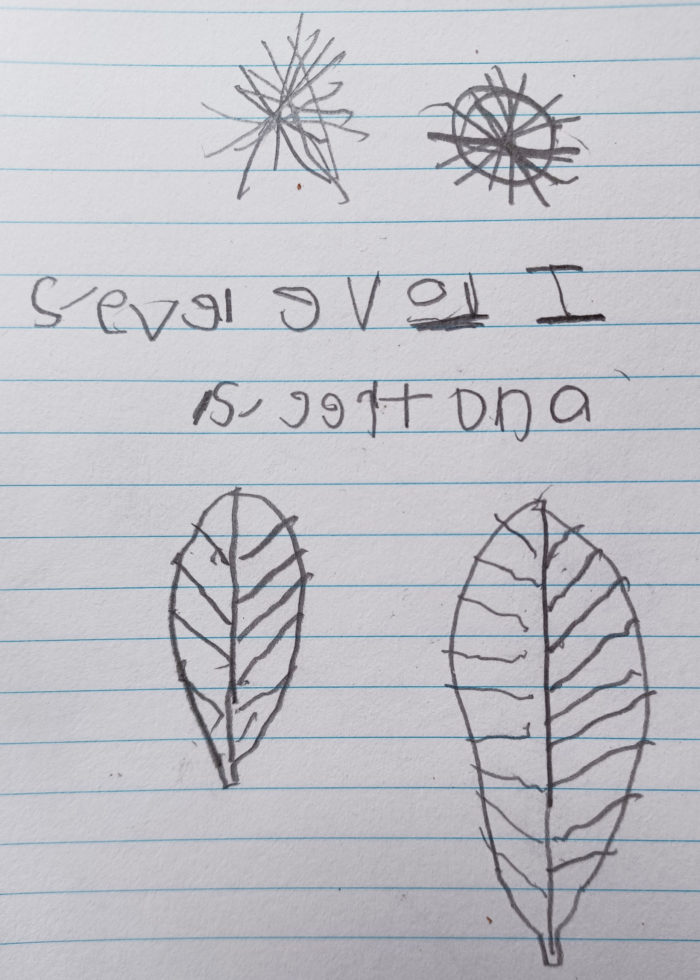

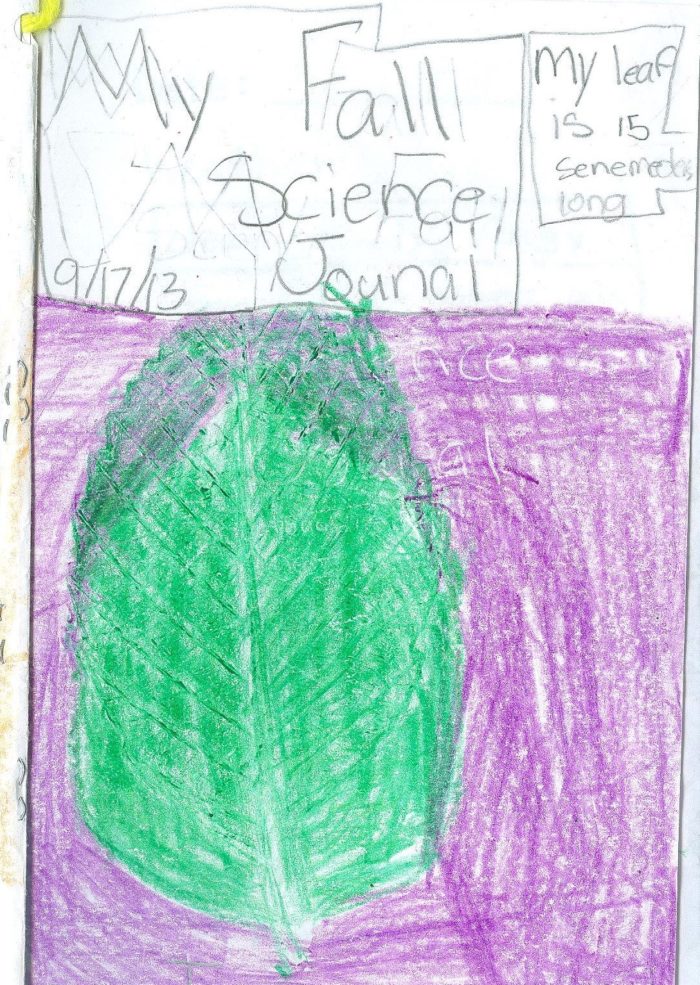

Measurement and Mathematics

Journal entries can be used to build mathematics and other basic skills like measurement. For example, the crayon leaf rubbing below was incorporated into a math lesson, where students measured the rubbings in their journals and compared the lengths of their leaves. This simple activity can be extended into a variety of explorations including:

- A discussion of the different types of leaves measured.

- Discussing what might account for their varied sizes.

- Calculating averages.

- A discussion of the leaf veins and how they are similar and different and their purpose.

- A discussion of symmetry/asymmetry.

Meeting Standards and Mastering Self-Expression

Nature journaling is also an engaging and low-cost way to address some of the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) using phenomena.

“By centering science education on phenomena that students are motivated to explain, the focus of learning shifts from learning about a topic to figuring out why or how something happens. For example, instead of simply learning about the topics of photosynthesis and mitosis, students are engaged in building evidence-based explanatory ideas that help them figure out how a tree grows.” Using Phenomena in NGSS.

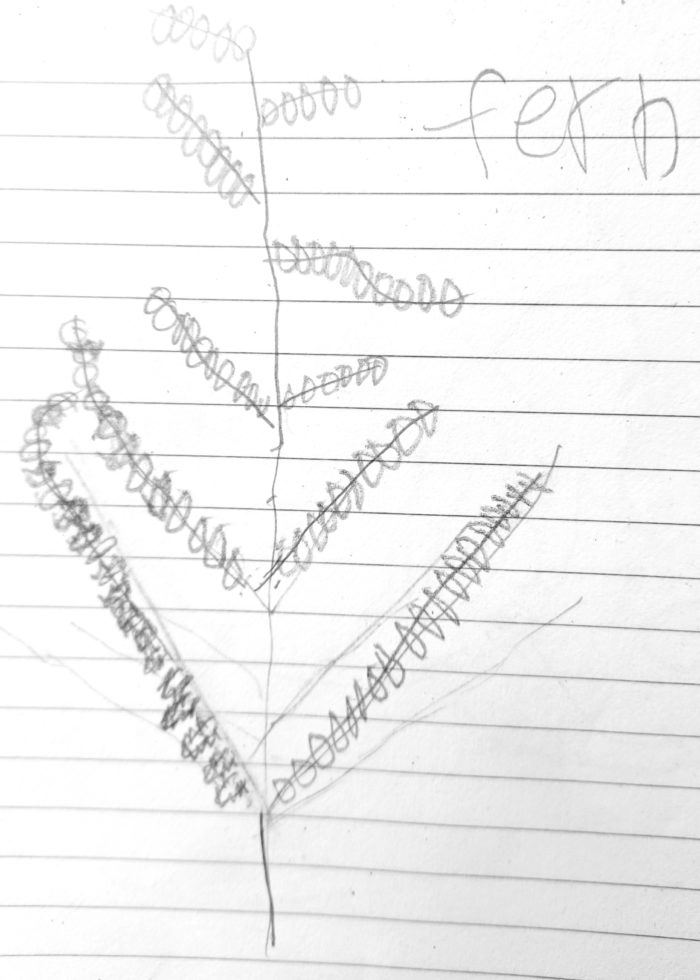

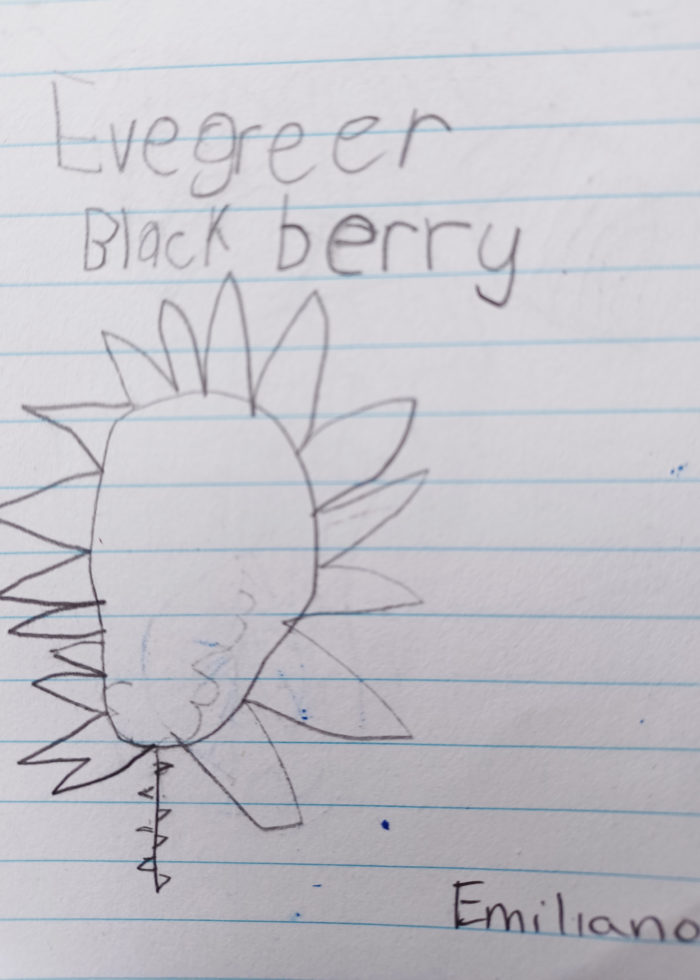

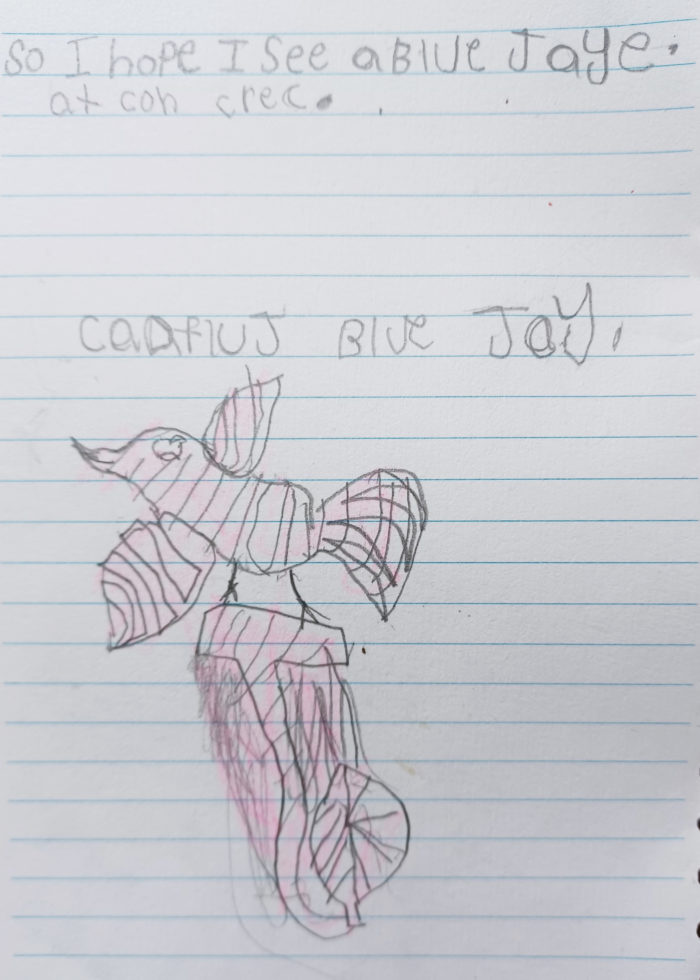

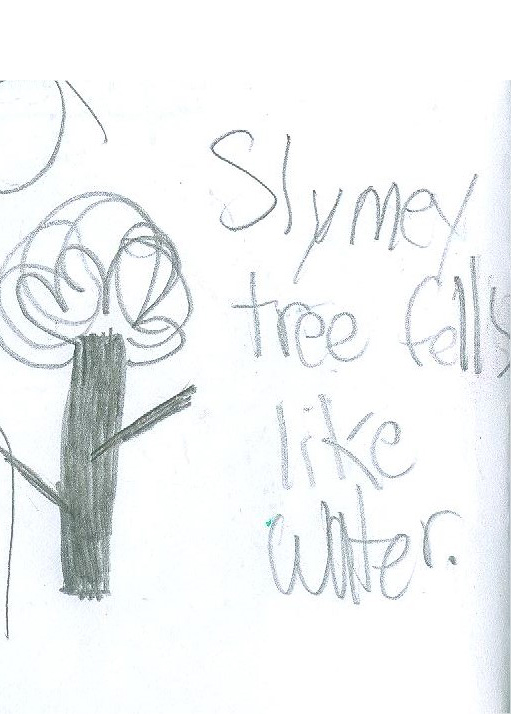

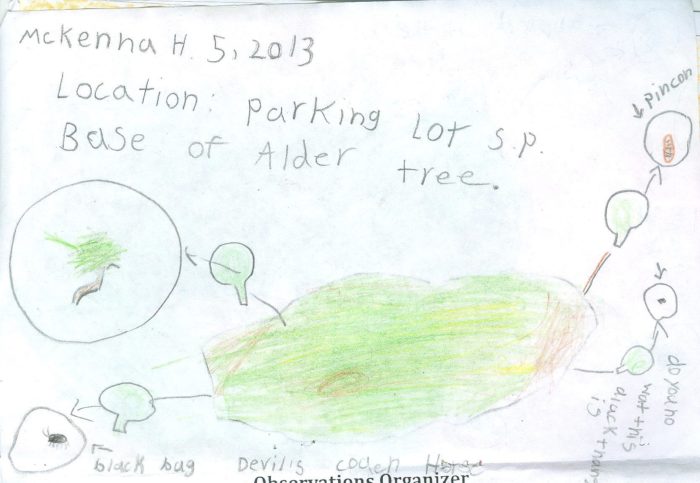

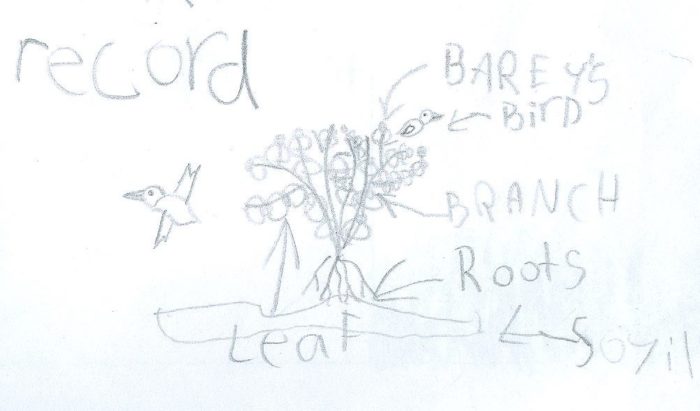

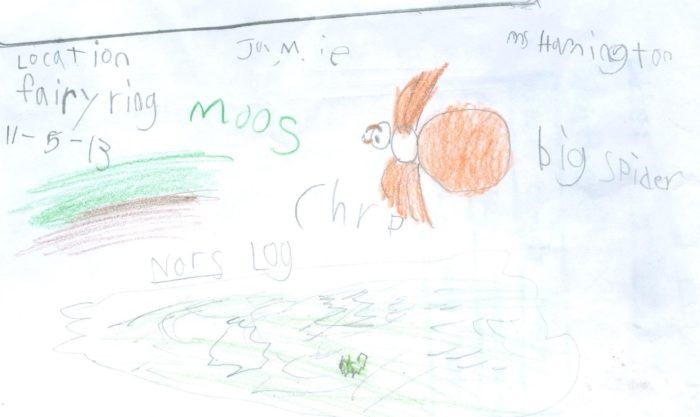

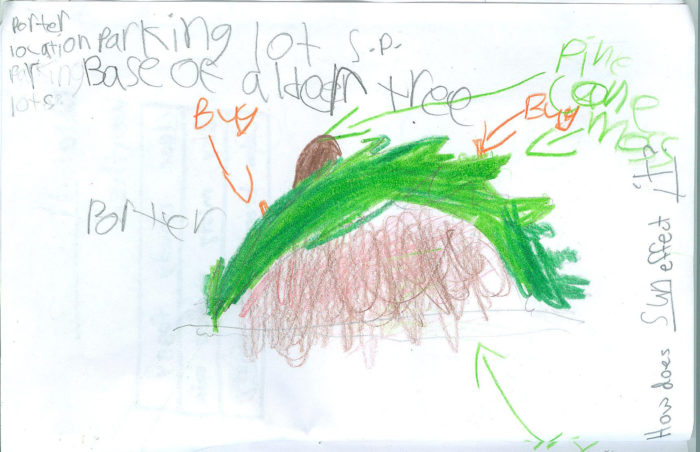

In the images to the right, one student was exploring phenomena and examining seed dispersal by observing and recording birds eating the berries of the invasive Himalayan blackberry bush. Another student documented a large spider and observed a nurse log. A third student noted the moss and pine cone found at the base of an alder tree and wonders “how does the sun effect [sic] it?”. Journal drawings can also give students the opportunity to compare the variety of life in different habitats and even begin to understand the role of stewardship in their communities.

Students of all ages, cultures, skills, and language abilities can develop a relationship with the environment that surrounds them through journaling, creating a personal connection beyond rote memorization of core ideas. While journals helped my second-grade students move toward performance expectations, I never assessed or critiqued their drawings or methods. Also, while it is possible to teach art concepts during journaling (which can help students learn to better express what they see), the focus here was to explore phenomena. As a result, I prompted students to add more details and to express aloud what they recorded in their journals.

Nature journaling also provides students an opportunity to engage with the NGSS Science and Engineering Practices. Entries can incorporate asking questions, developing models, planning investigations, analyzing data, using mathematics, constructing explanations, and engaging in arguments from evidence. Lastly, students can communicate their “published” journals with a variety of audiences including classmates, students from other districts, and adults.

Finding Free Gifts

Through journaling, I have seen students’ stamina for focused attention, in both the indoor and outdoor classroom, grow rapidly. It is beautiful to see a student’s eye caught by an abstract shape created from light and shadow or a never-before-seen insect. One by one, my students learned to journal using all their senses. By the end of the year, they were noticing and recording the sounds of bugling elk and the smell of a decaying baby bobcat.

As Annie Dillard says when she observes birds in Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, “These appearances catch at my throat; they are the free gifts, the bright coppers at the roots of trees.” The most important message I took from Dillard is that nature is everywhere and always there for you.

Equal parts science and art, journals are a first step for students to become stewards of the place in which they live. By observing and documenting the plants, animals, and features of where they live, they understand it better. Through deep knowledge comes appreciation, and ultimately a desire to protect the environment in which we live.

More Student Journal Entry Examples

Denise Harrington is the 2022-23 Teacher at Sea Alumni Association NOAA Fellow. She sailed as a Teacher at Sea in 2014 aboard the NOAA Ship Rainier and in 2016 aboard the NOAA Ship Oregon II. She welcomes any questions about this blog via email.

Denise Harrington is the 2022-23 Teacher at Sea Alumni Association NOAA Fellow. She sailed as a Teacher at Sea in 2014 aboard the NOAA Ship Rainier and in 2016 aboard the NOAA Ship Oregon II. She welcomes any questions about this blog via email.